Caldwell Cooperage Barrels Are Making Spirits Too

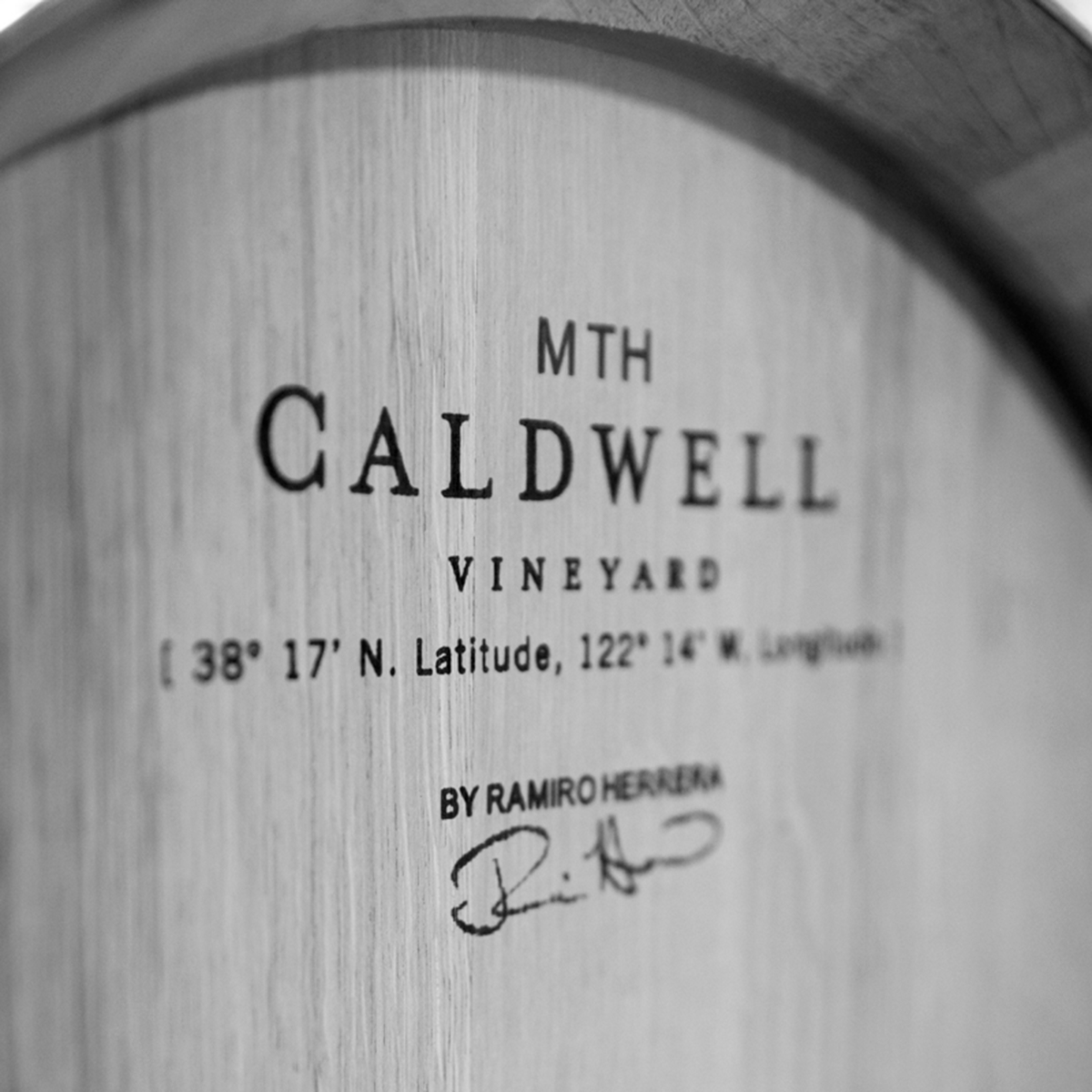

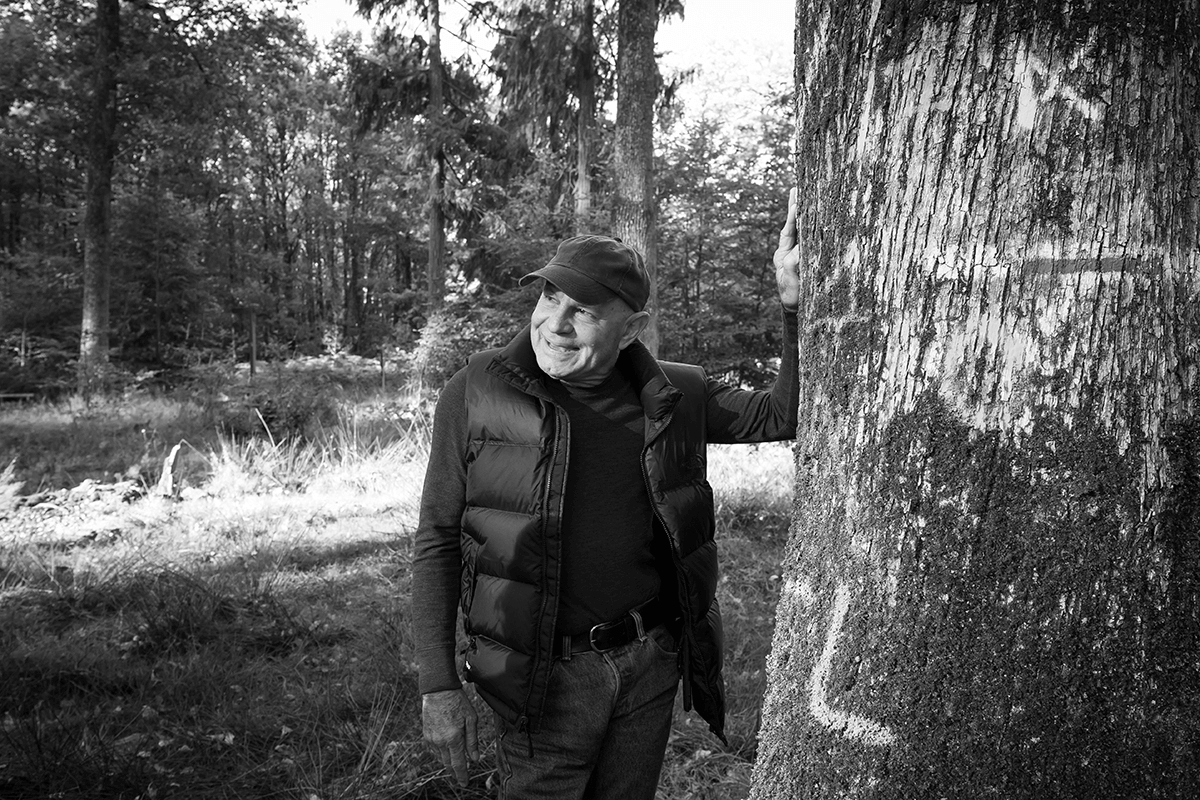

Turns out, just like wine and whiskey, tequilas get about 75% of their flavor from the barrel. The oak softens the mouthfeel and adds complexity to what otherwise tastes like any other pure spirit. Aging brings out even more of the flavors. So being a barrel guy, with our own Master Cooper on staff (Ramiro is the man), we didn’t just want to taste other people’s tequila, we wanted to make our own.

Our Master Cooper, Ramiro (who is Mexican himself), happened to know the owner of a tequila distillery in Amatitán, Mexico. So he invited the guys up to Napa to have a proper tasting at the winery. They brought their best stuff. It seems we were duly impressed because the tasting lasted ‘til 2am. I made it to bed that night, but don’t remember getting’ there. That night a partnership was born and JFC Tequila came to life.

“Why not make it ourselves?”, you ask. Well, you can’t call just any old blue agave liquor “tequila” unless its made in the right part of Mexico. Its just like sparkling wine can’t be called Champagne unless its made in Champagne, France.

After the tasting, Ramiro set to work hand-crafting barrels that would offer the absolute perfect flavor profile and then shipped the Caldwell Cooperage barrels down to our friend’s production facility in Tequila. Our winemaker, Marc Gagnon, went in person to make sure the right tequila got put in the right barrels so we’d have plenty of options for blending the final batch.

A couple of years ago, Ramiro got an email from a French girl he used to work with at a cooperage in Chile. Some of her Mexican friends were coming to Napa and wanted to meet him, so he invited them out for a tasting at the cave. Turns out one of these friends, Mauricio, just happened to own a tequila company in Jalisco. When they got home, Mauricio sent a thank you note, a few bottles, and an invitation to come visit anytime.

Two years later, I was itching to go to Mexico and asked Ramiro if he knew anybody down there. By a dumb stroke of the now famous Caldwell luck, our friend Mauricio just happened to be coming to Napa for another Caldwell tasting. He brought a little more tequila with him which we sat down and tasted with Ramiro, and our vineyard manager. When I tasted this stuff, I decided on the spot that I needed to head down and get a proper indoctrination into the world of Tequila. I booked and ticket for the following week.

Mauricio hooked us up and we tasted at a bunch of different places but, everywhere we went, there was nothing but old barrels.

Now, you need to understand, liquor gets 95% of its flavor from the barrel, and barrels only have about five, maybe six years where they’re giving their best aromas. When we asked why they were using these old-ass barrels, the answer was always that the new ones were too expensive ($40 vs $1000). So of course, we had to see what we could do if we aged this stuff in a proper Caldwell Cooperage new French oak barrel.

Ramiro got home and built a brand new 40-liter barrel from our stash of French oak, and poured 40 liters of Mauricio’s one-year-old tequila in there. Three weeks later, we did a blind tasting alongside Mauricio’s 12-year-old bottling. The baby tequila with three weeks in real oak won by a landslide – hands down. Are you fucking kidding me? We actually did another blind tasting beside a bottle of Pappy Van Winkle whiskey, and damned if the oak-finished baby tequila won again.

Since you can’t call your agave liquor “tequila” unless it was made in Tequila, Mexico (just like Champagne), we’ve now got about 10 barrels full of tequila down in Mauricio’s facility waiting to be bottled. Of course, the only name for the stuff is Pinche Caldwell (look it up).

Nulla quis lorem ut libero malesuada feugiat. Vestibulum ac diam sit amet quam vehicula elementum sed sit amet dui. Vivamus suscipit tortor eget felis porttitor volutpat.